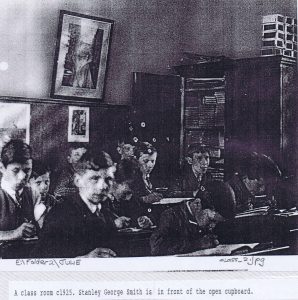

The Old Primary School, Henham in Georgian and Victorian Days

The photograph at left above shows a girl in black in the middle this is Clara Smith who is the daughter of William Smith commonly known as Postman Smith. Clara married Frank Barber, their daughter Jessie married Walter Cornell who was a Sidesman at the church and use to cut the church graveyard with a scythe (thanks to Michael Cornell, Jessie and Walter’s son for this information).

1825. George IV was on the throne — a selfish king, who contributed nothing to the effort his country was making to raise itself out of the exhaustion of the Napoleonic wars. The post-war fall in prices had ended; farms were being repaired and improved, cottages were being re-thatched. In Henham the Poor Rate was higher than it had ever been since the crisis year of 1801, when even the sale of ‘Portators’ went towards Poor Relief, but recovery was on the way, and Boney’s threat was over.

The background to those years of poverty and endeavour in an agricultural parish such as Henham meant that poor children who received any formal education might have done so through the Charity School movement, which began in England after S.P.C K. was founded in 1699. The Society circularised and urged the clergy to form a school in every parish, to teach the catechism to the children on weekdays, and to take them to church on Sundays. If funds permitted they should be taught to read and learn the Psalms; the boys taught simple arithmetic and the girls knitting, spinning, making and mending clothes. S.P.C K. has no record of a Charity school here, but there may have been an independent free school, for the parish in the early 18th century had a good vicar in Samuel Smith, a good Lord of the Manor in Samuel Feake, and fairly prosperous tenant farmers who may have supported a school by subscriptions as a voluntary additional Poor Rate.

The early 19th century was the hey-day of Nonconformity in Henham, but, as elsewhere, money raised by the two great societies concerned with education — the National Society, founded in 1811 for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, and the undenominational British and Foreign Schools Society would have found its way to a Church of England School. From National Society records, a school was established in a rented building in Henham in 1822. In 1825 and newly arrived vicar, the Rev George Glyn sent in two applications: one for union with the National Society, saying that its system of teaching was adopted and no religious tracts used in the school, but those in the catalogues of SPCK, for one of the first rules of the Society was that all affiliated schools must use only their publications. The second application was for aid for enlarging the School, for 100 boys and girls between 7 and 13 years old; instruction was to be free; the lath and plaster building would cost £85; the charge for the master and mistress would be £50 and added that efforts already made had totalled £10, and that “No further exertions could be made”. Financial help was forthcoming, and the School of clay and thatch was built in 1832-3.

In 1835 George Glyn redeemed the land – tax charges of Pledgdon hamlet. The sum was left in trust — £5 yearly for “a master to teach boys on the Lord’s and other holidays and to have the charge of them during Divine Service in the Church”, the remaining £1 was to be spent on religious books, and, the Deed continues, “the sum of £5 has been expended by Mr Glyn in aid of the Sunday Branch of the National School of the Parish, and £1 in the purchase of religious books for the use of the scholars”.

The village school was very much the responsibility of the Church and its parson, and the Glyn family were very conscious of this. From the Charity Boards in the Church we read that the reverend T. Clayton Glyn, carrying out the intentions of his brother George, gave, in 1848 a copyhold cottage and land called Snows, for the mistress of the School for Educating Children of poor persons of the parish in the principles of the Established Church, provided she had been appointed by the Vicar. From White’s Directory for Essex 1848 her name was Kitty Sprusen, and the School is described as “an old lath and plaster building”. The 1847 Census Return adopted by the National Society tells us more about it — a Sunday and Day School of 79 children in a population of 892. The school cost £40 a year to run, and the amount paid to the master or mistress, including children’s pence and coal allowance was £30. Thirty-three boys and girls were Sunday Scholars only. Everywhere the National Society had been compelled to relax its veto on Sunday – only schools, owing to the great demand for child – labour — farming an industry which needed their work, as well as parents who desperately needed money. These Endowments, planned to bring the children to church and teach them the Catechism and the simplest form of education, were fairly frequent in the previous century: These for Henham seem late. Always there was the conflict between the need to work, and the growing demands for learning, either from pressure or the child’s wish to learn, and always, always, with the poor, the narrow margin between reading, writing and food.

To illustrate this, in the late 18th century, two village boys, in other counties were growing up in almost illiterate families; lovers of the countryside — “this shining land”– who recorded its beauty for future generations. In Sussex , William Cobbett, one of the stalwarts of his period, was born to a mother who could not write, and a father who had spent his 2d a day plough money on evening classes. But book –learning was to Cobbett anathema without the ability to use simple things in the right way, and the commonsense and forethought which could make a cottage home hospitable and happy. On one of his Rural Rides he stopped at Goudhurst one August evening to hear a sermon on behalf of the National Schools: as he listened to the preacher and watched the uncomprehending Sunday School children he felt that words without feeling or persuasion were useless and that “this preaching for money to support the schools is a most curious affair altogether”. John Clare, visionary and poet of nature, was born into a Northamptonshire peasant home: his father could read a little from the Bible, but his mother was entire illiterate — a source of such regret to her that she determined that her son, with his zest for learning, should have whatever schooling they could manage, even in the hardest times.

It is obvious from Henham’s only surviving book of Vestry Minutes (1783-1848), that the Overseers, as well as the Vicar, were concerned with its education, and took their responsibilities seriously. There is “An Account of the Population of this Parish, taken October 22nd 1838 by John Mumford, churchwarden, which would appear to have been a local literacy test, for there was no Government census that year:-

Hamlet of Pledgdon Town Population

150 675 825

42 cannot read 283 cannot read

____

108 392

The proportion of those who could not write was even higher in the Church registers — almost 5 to 1 for the years 1831-1845. Unless there were some incentives, such as in John Clare’s old home, to one struggling to bring up a family in an overcrowded cottage “it shall be writ for you on a piece of paper” signified great effort, and provided there was an illustrated book or paper, one could always “read the pictures”. The Government Census for 1851, is more explicit, as enumerator, again John Mumford, went from house to house, getting full details of age, occupation and place of birth. It lists 21 boys, aged between 9 and 16 as agricultural labourers, who benefited from the Glyn bequest as Sunday Scholars. But lived a hard and relentless life, for children of nine and ten – the fields on a weekday, a little holiday on Sunday.

In 1853, the Rev Arthur Bellman was instituted, and campaign for a better school, better fittings and the great need for books, as these extracts from his letters show: –

November 1853. To the National Society. £50 has been collected from parishioners towards a new school.

Population 950. ” no resident squire, and the inhabitants are nearly all common labourers. Children at school would be about 170″.

December 1853. No pledge of aid was forthcoming, but he wrote optimistically that the Lord of the Manor would convey to him as Vicar of the Parish, a piece of land sufficient for two school-rooms and a master’s house. ” £60 has been raised with difficulty from a population entirely agricultural and very badly off”. A new school room was built, and exhausted all available funds, to which the only contribution had been £5 from the National Society, “and might I again beg a further contribution in the grant of some books?”.

The new building appears soon not to have been large enough, and after setbacks and disappointments, the Vicar was still contemplating in 1863 a new schoolroom of brick and slate, which would replace the 1832 building, which was not longer habitable:- to the National Society. “If I can raise £5 more a gentleman in this parish has intimated that he will build the new schoolroom and put the whole school in thorough repair. As I have already given £31.10.0 out of my private income and taxed the charity of the parish to the utmost I am inclined to think the National Society would kindly allow me the small sum, I require… the plans that were sent were far beyond our means”.

Ministering Children published in 1854 helps us to realise the poverty of village homes, the scarcity of books, the value put on the Bible, often the only book in a cottage, and how hard children had to work in Victorian England. ”Every ear of wheat that waved on Farmer Smith’s fields was sown by the hands of the village children…their little feet could pace the fields backwards and forwards, and not grow weary…their fingers could drop the precious grains from the little wooden basket held on their left arm… Three grains into each hole”, made by their fathers, walking backwards, with iron dibbling rods. When little Mercy’s parents died, she had to earn her bread under her grandmother’s care. The Poor, in this moving tale, dedicated to childhood, received loving charity, but equality was a long way ahead.

Almost all 19th century local records show the hard background of Henham life. From the 1840 Tithe Award it appears that 7 to 1 of the population owned no land, not even strips on the Commons, so when Enclosure of 630 acres was awarded in 1850. It did not have the same effect on the cottagers, as it did in the Midlands; in Essex the loss of their rights had come slowly and by degrees. The greatest impact of Enclosure came on the farmers; they would have been hard put to it to pay all the legal costs and huge sums for hedging and fencing, and that in turn reacted on their workers. A letter dated September the 21st 1859, from the second largest farming in Henham states: –

“Things must alter and agriculture must wear a more promising aspect or we shall soon, leave old Pledgdon Hall; the corn is blighted and selling at lower prices than last year”. Therefore farming depression continued to affect the village school, and its problems persisted as more extracts from further letters from Mr Bellman to the National Society show: — “The school is in the most dilapidated state”.

“The old school is mostly built of clay, which is now fast falling away”. “The Inspector remarked on the want of accommodation for the children when he last visited the school, and I believe he reported it to the Bishop of the Dioceses”. In May 1869, another appeal went to the Bishop of Rochester: –” The mistress, wife of one of the labourers, does her best. The eldest children answer intelligently, but they want books”.

However, the burden carried so long, and often with great self-sacrifice, was soon to be lifted. In 1870 the Liberal Government brought in Forster’s Education Act, which provided generous state-aided grants for parishes where help was needed, followed by a regular and certain income from the Rates. On June 1st 1874, a meeting of Henham ratepayers formed a School Board for the United Parishes of Henham and Chickney, with a call on the Overseers of both parishes, and the new school, of redbrick and slate, with a bell- turret at one end, built at a cost of £920 by George Perry, architect, of Bishops Stortford, and George Wiffin, builder, of Saffron Walden, arose on the site of the old Sunday School Room, and on the waste in front. It was open on February 14th 1876, to serve a century of Henham children, and later a further piece of waste in front was granted by the Lord of the Manor as a layground. The house next to the School was rented at £7 a year as a residence for Miss Allen, engaged “to conduct this school at £75 per annum”, with an assistant mistress at £35 a year, and a monitor at one shilling a week.

A new mistress and a new school. When the carriage deposited her and her belongings at the gate of a new home there must have been much speculation from those looking over their gates across the Green. As she surveyed her 128 pupils on the first morning did she feel like Jane Eyre on her first morning in her village school at Moreton — “weakly dismayed at the ignorance, the poverty, the coarseness of all I heard and saw around me… Tomorrow, I trust, I shall get the better of them partially.. and in a few weeks, perhaps, they will be quite subdued”. Elizabeth Allen on her second day classified the children into four groups, and the pattern laid down for her by the Board began to take shape. After assembly, the School prayers: a hymn or Scripture reading, or a lesson (non-sectarian) for half an hour. Then, basically, the three R’s, reading, writing and arithmetic. The weather was bad, attendance dropped, she found most of the children entirely ignorant of arithmetic, and apart from her monitor, for three weeks she was single-handed, and she began her formidable task.

Books were always short, and there seems to have been little money available for them. A year after the school opened the School Board was trying to obtain books from the Book Depot, Borough Road, London, on the three months’ credit basis. Sometimes the Vicar’s wife took a class for reading; the Chapel minister, a constant visitor, examined and taught both reading and writing.

From the Log Book 1876. The third class is still very backward in all three subjects. The Reading is particularly bad; the cause is that the earlier part of the year was occupied with learning letters and the most simple words from an Introductory Reading Book.

The fault was not always the children’s: –

1878. I examined the Fourth Class in reading, but I’m sorry to say the results were far from credible to the teacher’s abilities as a teacher. 1880. The pupil-teacher received no lessons this week having no books to work with. 1895. They can be no doubt that the children need to be taught on more intelligent lines. (Her Majesty’s Inspector).

Sometimes the children were praised: –

1891. Reading throughout the school was commendable.

Criticism could bring other problems:-

1897. Examined First Class of Infants and pointed out need for attention. One girl absent all the week because the mother has taken offence. Like books, material for writing was scarce; everything had to be obtained through the Board: –

From the Minute Book 1877, Ms Allen came before the Board and asked to be supplied with pens,

exercise books and papers. On the whole, writing seems to have been one of the be better subjects: –

1876. The Reverend A. H. Bellman examined the Dictation of first-class and expressed himself satisfied with the result.

1880. The scholars are under satisfactory discipline and their examination exercises were executed with commendable neatness. (HMI report).

Countering the “entire ignorance of arithmetic went on energetically, but with the somewhat unencouraging methods of time.

From the Log Book 1880. The First Standard are very must behind in their tables, so I have arranged for them to repeat them. Three extra time during the week, hoping they will improve by the next month’s examination.

1884, the weak points are Mental Arithmetic throughout the school.

1886. The children’s habit of using fingers as aids to working sums must be discouraged. (HMI

inspector),

1897. Children in Standard four and five are very backward indeed. They use their fingers in working simple addition sums. They were taught to add that way when infants.

At that period there was a change in Headship after the sudden death of C. J. Housden, “a faithful servant of the Board and ratepayers”. Judging from the muddled Log Book entries and erratic writing. One wonders what will the capabilities of the new Headmaster, and whether “the extraordinary dullness of the children” and “their extreme lack of intelligence” was theirs or his:-

1897. A girl 14 years old and Standard six is unable to answer such questions as – “If a man does half of a certain amount of work, what maybe found out from that?”.

A J Legge, and his sister only stayed two years, to be succeeded by Benjamin Hood. He quickly remarked, “the children are beginning to be alive to the necessity for work”, helped, it is known by knotty hazel-nut sticks, which the older boys were sent to cut in Lambert’s Meadow.

The school building, for 152 children, was based on one large room with a smaller room for infants to the north, with a gallery at one end. Only six years after the School was built the Education authorities required an extra classroom as, from the Minute Book, “in their Lordship’s opinion, the attendance exceeded the capacity for which the school had been planned”. In vain the School Board protested that the average attendance,142, had not even reached the initial figure, and begged that the plan need not be carried out ” especially in the present depressed state of agriculture (the School district being entirely agricultural)”; the Education authorities turned a deaf ear, and threatened unless the work was carried out the annual Grant would be withheld. The work was immediately put in hand, the cost, over £ 200, being covered by a loan from the Public Works Loan Commissioners. And,1885, ” the new Classroom is a great improvement”.

Memories still persist of the gallery in the infants room, about eight or nine steps high, and how the small children used to fight so they could sit on the coveted top form. The benches were so close together that before backs were fixed, the children’s clothes were dirtied from the boots of those behind them, so, advised HM Inspector in 1880 — “ The gallery seats should be furnished with rests for the backs of the children: the infants need a supply of good slates”. No infant gallery was allowed to hold more than 80 or 90 children, but observerd HMI in 1895 — ” The occasional tendency of the younger children to restless movements or murmurings should be checked”. After 1896 the packing together of children on benches was almost a thing of the past. Not even the writing on slates of rows of pothooks and hangars ( lines of long strokes attached to a U ) or copying large letters, could be accomplished if there was nowhere to put your slate, later wiped clean with split, coat -sleeve, or pinafore. Henham was never very keen on innovations and the gallery persisted into Edwardian days: ” The gallery is an awkward construction”, states the Log Book of 1904, and ” The managers met this evening and agreed to have gallery in Infants Room removed and new desk put in place”. Progress at last. Not however as regards water (which was not piped to the village till 1938).

The School depended on the pump on the Green for water; a bucket and bowl in the porch for washing, and the children on their cupped hands for drinking. Yet from the Letter Book, July 9 1897, the following went to the Parish Council. ” Gentleman. At the meeting of the School Board on the 7th. inst. I was instructed to draw your attention to the Pump on the School Green. The water is unfit for drinking purposes and the Board are of the opinion that if the well is cleaned out it would very much improve the water “. So perhaps, in summer droughts, it was a good thing when the pump was chained up, and water unobtainable, and long- distance children called at various friendly cottages, for a drink of water on their way home.

When the School opened, weekly payments for farm workers’ children were 2d for the first child, and for every other, 1d. Little enough, but it had to come out of 10 shillings or 11 shillings a week’s income for the whole family. There was always the incentive to keep a child away from school to work for the farmers, or to look after smaller children while the mother went out to fieldwork or washing for the day.

Applications to do this were refused by the School Board, caught between their duty to enforce attendance, and the needs of the family. The Church Registers, figures for infant mortality ( to the age of four years) for a 50 year period that century, show one death every four months, and of those, eight were babies burnt of scalded to death; small room with big open fires and kettles on the hook were a terrible hazard without constant care, it possible to a harassed mother, or very young child-minders. Log Book. 1895. The attendance has been very irregular as Mr Duckworth (Parsonage Farm), has employed about 60 persons, to pick his peas, and the children are wanted to take care of the little ones, while their mothers were away. Soon after the School opened in 1879, the fees were to be raised after the harvest to 3d for a farm worker’s single child, 2d for the next two, and 1d for all others; tradesmen to pay 3d to 9d. This decision was followed by the most disastrous harvest of the century; by the end of October gleaning had not yet finished. Following the bad harvest, many parents refused to send the extra fees, although with all the poverty and hardship they were reduced in November back to the Spring level.

Disruption and revolt continued into the next year, some parents appealing successfully to the magistrates. Sometimes, children whose parents could not pay, was sent home from school: in 1882. A whole family went to the Workhouse. A few years later, a great burden was lifted from many poor families all over the country, when in 1891 the Free Education Act abolished the contentious “school pence”; the local School Board accepted a Fee Grant, and henceforth education at Henham School was free.

The yearly visit of Her Majesty’s Inspector was the most anxious and important occasion; on his report depended the Grant to the Board, and the Head’s reputation. He would inspect the official School books and Registers – 1898. (There must be no erasures in the registers), look at the children’s work, mostly on sheets of paper from scarcity of exercise books, and examine them. In the words of a late scholar –

” We were scared, stark stiff: real windy”, as they sat waiting on forms or in their double desks, in uncrumpled pinafores, clean shoes and jackets. Very often extra equipment, such as slates, desks, Globes, and a recommendation for a harder Reading Book resulted from his visits. The first reports, 1877, remarks: — “The buildings and appointments of this new school are very good, and display much forethought on the part of the Board… The mistress shows laudable energy… that progress has been, and must yet be, uphill, both as regards discipline and instruction; a good beginning is made”. The next year – “handwriting and spelling are very creditable, the Reading should be more distinct and animated. The mistress handles the School well, and will, I hope, overcome the copying which now exists to a great extent”.

His reports give the impression of a well-behaved, and well-conducted School — “the order and tone are most pleasing: the general spirit of activity and cheerfulness are most creditable to the teachers” – A School better at discipline than learning, using unimaginative methods at a slow country pace. The Reports constantly stressed the importance of early training for the Infants –

1878. More infants should be brought in, and shall be forwarded.

1898. It is in Infants’ Room, where habits of obedience and self-restraint are formed, and this important part of the child’s training must not be overlooked”

In March 1881, came a most depressing report: – ”The discipline of the School is fairly good, but the Instruction is very defective in all subjects. My Lords will expect a more favourable report on the Instruction of this School next year, as a condition of and unreduced Grant “. The teachers had been working against great difficulties, illness, absenteeism, and the effects of the great January snowstorm, Black Tuesday, which caused Elizabeth Allen to write one of her rare Log Book entries about the weather — 18th. attendance was not taken this afternoon in consequence of a severe snowstorm. 19. School closed all day. Children are not able to come; the roads are impassable with snow. 20th. Only 56 children were present in the morning, and 70 in the afternoon.

Elizabeth Allen was unlike her successor, whose entries were almost entirely concerned with illnesses, and the weather; entered or not, it had a great effect on School attendances, particularly to children walking from Pledgdon or Little Henham. An entry for as late in the year as May (1886) states; “most of the children are now at School, having recovered from the effects of the severe winter”.

1889. A deep and drifted snow today: only three children who live very near the School were present.

1891. A snowdrift 4 feet or 5 feet deep course were Pledgdon Green children to stay away.

After accounts of wet and flooded roads, in January 1901, came a most tragic entry –

“One of our boys died on December 21 from acute inflammation of the lungs. This is a sad case of a boy being badly provided with boots “. The Log Book’s record efforts to help the parents and children with the great problem of shoes, which could prevent children from going to school. In the autumn of 1887, the Lord of the Manor, Salisbury Baxendale, and his son distributed shoes from the School Shoe Club, and later the young squire, known as Sarum distributed more shoes. A later scholar recalled, that whatever his shoes, they had one thing in common, they all let in water when it rained.

As well as wet feet, from trudging through mud and slush- the Green and so-called paths around the School are simply pools of mud

” — illnesses from damp and cold, such as coughs, colds, croup and chilblains were the usual results from damp and drafty cottages, and an entry for December 1887 when Salisbury Baxendale gave away gifts of 18 blankets at the School must have meant a very important occasion. There are constant entries of bad and sore heads. Occasionally serious hazards like pneumonia, scarlet fever or typhoid, or fatal accidents, such as:- 1877. One of the second-class boys met with a fatal accident on the Line”, and 1886 days, – “A Scholar in the fifth Standard, accidentally shot himself in the stomach and died a few minutes afterwards”. To end on a lighter note, from a later headmaster: — “I am sick and tired of drying children who have fallen into the ponds’.

There were also the bright and sunny days, when the children played a long to school, spinning their tops, bowling their hoops, bought for 1/2d. from the village blacksmith, and eating off the land — blackberries, sometimes duck or hen’s eggs, fresh corn, a turnip, all nibbling from the hedgerows’ plenty. One who came from Pledgden Green at the turn-of-the-century remembers coming up Carter’s Lane, in winter mornings, she and her small companions in bonnets, capes, muffs and heavy shoes, tipped and nailed, walking and slipping through the grass and frozen puddles, carrying their bread for lunch in little drawer- string calico bags. In the dark afternoons, “the children who live far out into the country are obliged to leave early, otherwise darkness overtakes them before they can get home”, — many had over 2 miles to go. If the girls were alone, they had been well-trained by their mothers — ” Popsey – would you like a lift?” ”No thank you sir. My mother said I was not to ride with strange gentleman”.

The harvest and the fields constituted Henham’s life. A boy growing up in the School had little ambition, but to work on a neighbouring farm, as his family had done for many generations. Right through the year there was fieldwork that a child could do, often to the dismay and aggravation of the School Head. In autumn, gathering and storing the potatoes from allotments or the rows allowed to men by the farmers, (an average family would eat about a tonne a year); ‘brushing’ for the beaters at Elsenham Hall shoots; pea or currant picking; Bird-scaring; in a hot, dry summer fire-watching on the Elsenham line near the corn-fields, and most important of all, gleaning, and helping their fathers, who would have a day’s holiday to thrash and store the gleaned corn, stored in sacks in the bedrooms “under the eaves where the thatch came down deep, for there wasn’t nowhere else to set them”. The “Harvest Holiday” last 5 weeks. One of the half -holidays granted was in honour of an earlier age, “in commemoration of Guy Fawkes’ Day”, a survival of a state service for November 5th, celebrated for the last time in 1858. There was a half-holiday, on April 10th 1894, when the Log Book tells us “a Confirmation was held for the first time in Henham Church”. There were the annual summer treats in the meadow at the back of Parsonage Farm, and holidays for two Jubilees, particularly for the Golden Jubilee in 1887: — August 3th and 4th ” A Jubilee treat was given to the schoolchildren and the women and girls of the parish by Salisbury Baxendale, Esq. and the young squire, at the Lodge. Each child received a Jubilee mug in commemoration of the Day “. Before the Diamond Jubilee Salisbury Baxendale had been forced through agricultural depression to sell the estate; there was no grand treat at the Lodge, though the children had tea, sports and a medal. A Christmas treat to which the children would look forward for weeks brought gifts from Walter Gilbey of Elsenham Hall (created baronet in 1893). This had been a tradition since 1897 — in the early days new threepenny pieces, in the later ones, oranges as well.

In the early Log Books there are many mentions of singing lessons and learning hymns by heart: after 1872 the attendance grant was reduced by one shilling, unless music formed part of the curriculum, and later the full amount was only paid if music was taught by note: if taught by ear, 6d. One of the earliest purchases by the Board was a harmonium for £6, and there were many formal visits by the Vicar and his wife, “to hear the children sing”.

We have the names of the 12 songs learnt every year, and the recitations set for the infants. Some of the songs will always be well-known — the Keel Row, Home Sweet Home, and Ye Mariners of England. The words of others have almost disappeared — The Snail; Little Nellie; Old John had an Apple Tree, and The Little Scare-crow. One hymn is still remembered: –

Little drops of water,

Little grains of sand

Make the mighty ocean

And the beauteous land.

Little deeds of kindness,

Little words of love,

Make our earth an Eden

Like the heaven above.

Among the infants’ recitations were — My Pretty Little Robin; The Hobby Horse; Tommy and the Apples. Also learnt for examination:-

Lazy sheep, pray tell me why

In the grassy fields you lie

Eating grass and daisies white,

From one morning til the night?

Everything can something do,

But what kind of use are you?

Nay, my little master, nay,

Do not serve me so, I pray;

Don’t you see the wool that grows

On my back, to make your clothes?

Cold, and very cold, you’d get

If I did not give you it.

(words supplied by later Henham schoolmaster, Hubert Doe)

Singing was part of village life before motors and tractors took the place of horses; You did not whistle or sing to an unresponsive object – a Horse of Iron. So the children heard their father singing, as they drove the wagons along the lanes:-” for to plough and sow, for to reap and mow, and be a farmer’s boy… and be a farmer’s boy”, and later on, songs of the Boer War.

The school life, we have covered was a very small expression of the Victorian era — a way of life finally ended by the 1914 War. The school building was the background to both good and bad: sometimes order, sometimes disorder; the rough days; the simple treats; repetitions over and over again — RAT – rat: CAT- cat.

Geography taught by Globes; lack of books, water and proper sanitation; games on the Green; hymns and songs; a stiff upper lip under corporal punishment (”a terror he was”): tributes to their teachers from old pupils – ”I am positive that what I achieved through life, and the way my character was moulded into shape, was done in that village school”.

The sole laconic Log Book entry for August 4, 1914, showed no comprehension of the world – wide struggle ahead — ” Elsie M Turner commenced duties as Infants teacher”, but it both closed and ushered in an epoch. She was to teach at the School, first as Miss Turner, then as Mrs Searles for 43 years. The final war-time entry is ringed round with red chalk:- November, 11th 1918. Received the glad tidings at 1230 that the Armistice had been signed and hostilities ceased. I invited the Chairman to come into school and lead us in a Prayer of Thanksgiving to God, for the blessing of Peace. After singing a hymn, and cheers for the King Soldiers and Sailors, and “our boys”, and the Prime Minister, sent the children home to convey the good news to their parents.